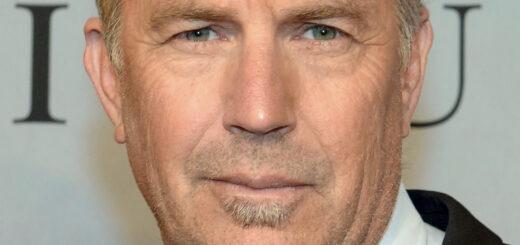

The Last Cornball American Director: Kevin Costner

If you’re an animal in a Kevin Costner-directed film, beware: your survival chances are slim. The Oscar-winning director has a recurring motif—his heroes often form deep bonds with loyal animals like horses, dogs, or wolves, creatures that symbolize freedom, innocence, and purity. But inevitably, these beloved animals meet tragic ends, usually at the hands of the film’s villains. This grim pattern reveals something about Costner’s filmmaking: his desire to hit audiences in the emotional core and his worldview divided sharply between good and evil.

From early on, Costner embraced an earnest, straightforward everyman persona. While he showed some swagger in “Bull Durham,” most of his roles—like those in “The Untouchables,” “Field of Dreams,” and “JFK”—were played by men who were unassuming, duty-bound, and sometimes a bit square. These characters aren’t flashy or “cool”; they’re driven by a sense of purpose that others might mock or misunderstand. For Costner, their unwavering zeal and quiet dignity are heroic, even if they sometimes verge on corny or outdated.

This tension—between being heroic or hokey, timeless or out-of-touch—makes Costner a compelling figure. Though I’ve never met him and can only judge by his work, his directorial projects distill his essence into pure form. They may not always be great movies, but they reveal his willingness to lean into his “cornball” nature.

His directorial works—“Dances With Wolves,” “The Postman,” and “Open Range”—are all Westerns. Each features him on horseback, gazing at the horizon, wrestling with an ineffable longing or perhaps escaping his past. The sweeping orchestral scores and epic visuals set the stage for ordinary men stepping up to extraordinary calls. They embody decency, honor, and the belief that anyone would do the right thing in such moments.

“Dances With Wolves” remains his crowning achievement, winning seven Oscars including Best Picture and Director. While it famously beat out Scorsese’s “Goodfellas,” the film holds up as a sincere and respectful portrayal of Indigenous peoples, grounded by Costner’s humble charm. His character, John Dunbar, transforms from a disillusioned soldier into a man reborn within the Sioux community. Despite some criticism for being overly sentimental or idealistic, the film endures for its heartfelt portrayal and continued cultural relevance.

Costner’s heroes are never villains; even when flawed, they retain a core decency. This earnestness made “Dances With Wolves” resonate, as Costner became a modern embodiment of American integrity, akin to Jimmy Stewart or Gary Cooper. His simple, genuine style offered a balm to a cynical world.

However, by the time Costner directed “The Postman” in 1997, that straightforward charm had begun to falter. After mixed successes and failures like “Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves” and “Waterworld,” his heroism in “The Postman” felt more forced, self-aware, and less authentic. The film’s ambitious attempt to be a Frank Capra-esque tale of hope in a post-apocalyptic America fell short, hampered by a convoluted plot and earnest, but clunky execution. Its nostalgic, idealized vision of America was well-intentioned but ultimately naive, and the finale’s statue-raising homage to Costner’s hero felt overly grandiose.

Following “The Postman,” Costner’s career slipped, with several box office disappointments. Still, he returned to directing with “Open Range” in 2003, a quieter Western that felt like a course correction. Classic and old-fashioned, it showcased a more restrained Costner, focusing on honor, friendship, and standing up to evil. The film’s story of aging cowboys confronting a ruthless rancher—and the death of a loyal dog—reaffirmed Costner’s devotion to themes of moral clarity and decency.

Costner’s affinity for Westerns—whether directing or acting in them—stems from the genre’s inherent code of ethics, which separates right from wrong and champions individual freedom. Even in the near-future setting of “The Postman,” he envisioned a world where a man on horseback could inspire hope. His portrayal is less about rugged masculinity and more about sensitivity—the “sensitive cowboy.”

That sensitivity defines his directorial work. “Open Range” quietly meditates on aging and legacy without the bleakness of other Westerns. It’s a hopeful fantasy where justice is served, love blossoms, and good triumphs over evil. Sometimes, Costner’s corniness means embracing the dream rather than dwelling on harsh realities.

While Costner’s films can be emotionally heavy-handed—even cringe-worthy at times—they remain earnest, sincere, and uniquely his own. His faith in inherent goodness and decency in people, though sometimes cheesy, strikes a chord. “Horizon,” his newest film, may face criticism, but no one doubts the passion Costner pours into his projects. He’s unapologetically committed to telling stories that celebrate the best, if sometimes corny, parts of us all.