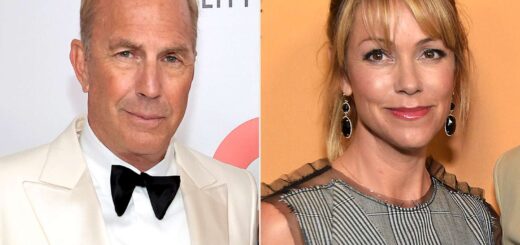

Kevin Costner on Nature: Conservation, Camping, and His National Parks Docuseries

“The Earth Is What We All Share”: Kevin Costner on Conservation, Camping, and His New National Parks Docuseries

“Countries are divided in so many ways, but the Earth is our common ground—and we keep missing that truth,” says Kevin Costner.

More than a century ago, on March 14, 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt wrote a personal letter to naturalist and early conservationist John Muir. He asked Muir to take him into Yosemite National Park—alone. “I do not want anyone with me but you,” Roosevelt wrote, “and I want to drop politics absolutely for four days and just be out in the open.”

The two men embarked on an unforgettable camping trip, which helped shape Roosevelt’s lasting conservation legacy. He would go on to protect over 230 million acres of public land and establish the U.S. Forest Service. That historic journey is now the focus of Yellowstone to Yosemite, a new docuseries on Fox Nation hosted by actor and filmmaker Kevin Costner.

For Costner—who played Lieutenant John Dunbar in Dances With Wolves and is no stranger to stories about the American frontier—the project is both a personal and patriotic tribute. “There can be no place like this Earth,” Dunbar wrote in that 1990 film. At 70, Costner brings that sentiment to life again, as he retraces Muir and Roosevelt’s path through Yosemite, from the granite monolith of El Capitan to the thunderous Yosemite Falls and the sweeping view at Glacier Point.

Along the way, Costner dives into the geology, wildlife, and the painful history of the Ahwahneechee people—who lived in Yosemite Valley for over 7,000 years before being forcibly displaced.

We sat down with Costner to talk about the inspiration behind the docuseries, the challenges facing conservation today, and the lessons that come from sleeping under the stars.

What drew you to this story and made you want to explore it deeply?

I’m someone who looks for patterns in history. And when I read about Roosevelt’s trip to Yosemite, it struck a chord. The fact that he just vanished from his campaign trail for several days, with no press, no entourage—just him and Muir—it’s wild. That kind of thing doesn’t happen anymore.

At the time, America wasn’t thinking environmentally. The country was still expanding. Land was something to take, not protect. Yet here were these two men—one a quiet thinker, the other a larger-than-life figure—coming together to say, “No, this place matters. Let’s save it.” That kind of moment deserves to be remembered.

You also highlight the story of the Ahwahneechee people. Why was that important for you to include?

Because we can’t talk about a place like Yosemite without acknowledging the people who were there first. We have this incredible national park—but it came at a cost. I don’t want to shame people; I’m not trying to beat anyone over the head. But we have to tell the whole story. That’s how history becomes honest.

It seems so obvious now that protecting these places was the right thing to do. But it wasn’t obvious then.

Exactly. We take it for granted that national parks are protected. But back then, even after something was declared a park, there was no infrastructure to enforce it. People still exploited the land. That’s why Roosevelt and Muir’s work was so visionary—they thought not just about preservation, but how to preserve.

It’s like when cars first hit the road—people were crashing, getting into fights, ignoring the lights. Eventually, someone had to step in and create the highway patrol. That’s what Roosevelt did for the parks. But today, we’re seeing ranger numbers cut when we actually need more. We still have a long way to go.

You’ve said conservation is patriotic. What do you mean by that?

When we choose to protect something for future generations, that’s an unselfish act. It’s about legacy. It’s saying, “I may not live to enjoy this forever, but someone else will.” When a kid from the city walks into a redwood forest and sees what the first explorers saw—that’s powerful. And it only happens because someone stood up and said, “Let’s keep this safe.”

You grew up camping. How did those early experiences shape your love for the outdoors?

We couldn’t afford hotels, so camping was what we did. My family would throw sleeping bags in the car and head to the Sierras, the redwoods, Yosemite. When you camp, you become part of the environment. If it’s cold, you build a fire. If it’s hot, you find shade. You stop running on a clock.

It teaches you self-reliance, but it also changes your rhythm. And then on the drive home, you find yourself asking, “Why don’t we do that more often?” It sticks with you in a way that nothing else does.

Do you still make time for those experiences now?

I do what I can. I take my boys hunting, diving, fishing. I’m flying out at midnight to Cuba to dive on a historical shipwreck I’ve been researching. That’s part of a story I want to tell too. Anytime I can get out into nature, I take it.

You joked in the docuseries that you’re not much of a hiker—so maybe no plans to walk John Muir’s path from Kentucky to the Gulf of Mexico?

[Laughs] Probably not that one. But the beautiful thing is you don’t have to walk every mile to connect with what Muir experienced. You can read his words, go to the High Sierras, sit in the same places he and Roosevelt did. Let the land speak to you. And if it does, you’ll bring someone else there. That’s how it starts. It ripples.